7 Popular National Dishes That Basically Define Certain Countries (But Actually Come From Entirely Different Ones)

Fact: Tomatoes didn't even grow in Italy until they were brought over from Mexico.

In my humble opinion, one of the most thrilling aspects of eating (or cooking) is that there's a seemingly endless supply of cuisines out there to learn about and sink your teeth into. Literally.

Recently, u/4L3X95 asked redditors to share some "national dishes" that are actually inspired by (or directly from) entirely different countries. As a total food nerd, I must confess — I was endlessly captivated. These are some of the most fascinating examples, spanning multiple countries and continents.

1. FACT — Modern-day tempura, a delicious staple of Japanese cuisine, actually came from a popular Portuguese green bean dish.

Yep, Japanese tempura actually has Portuguese roots — Portuguese missionary roots, to be specific. In the mid-1500s, Catholic missionaries from Portugal ended up on the Japanese island of Tanegashima after their ship was swept off course. The missionaries were ultimately banished from Japan in 1639 (when Christianity was determined to be "a threat to Japanese society"), but they left one incredibly important piece of their culture when they departed: a recipe for fried green beans known as peixinhos da horta.

The Japanese word tempura actually comes from the Latin tempora, which refers to the Ember Days, when Catholics abstained from eating meat. This traditional dish of battered and fried green beans was commonly eaten in Portugal during those times. Over hundreds of years, the recipe for peixinhos da horta was adapted by the people of Japan to become the tempura we know and love today, which has a lighter, airier fried coating than the former.

2. FACT — Italian tomato-based sauces as we know them only exist as a result of bringing the tomato, a crop native to the Americas, to Europe in the 16th century.

Considering the fact that thinking of Italian food likely conjures up images of al dente pasta and vibrant, flavorful tomato sauces, you'd probably be surprised to learn that tomatoes actually aren't even native to Italy — or Europe, for that matter. Until the 1500s rolled around, tomatoes were solely found in the Americas, until tomato crops were brought back to Europe by Spanish colonizers.

When the Spanish first set foot in Mexico in 1519, "tomato sauce" was already being sold in many of the Mexican markets. Though the ingredients weren't entirely identical to the tomato sauces we'd now associate with Italy — the Mexican versions almost always featured peppers, which aren't frequently found in most Italian sauces — it did ultimately inspire the Italian tomato-based sauces of modern Italian cuisine.

3. FACT — The bánh mì (a vibrant Vietnamese sandwich) came to be only after France's brutal colonization of Vietnam ceased in the mid-1900s.

Saying that the French "brought" baguettes to Vietnam leaves out an important part of history — France's imposed rule over the country following an 1862 peace treaty. As part of France's merciless colonization of Vietnam, they attempted to introduce French crops to Vietnamese farmland so they could continue to eat staple foods without the expensive overseas shipping — like baguettes and coffee. However, wheat simply wouldn't grow in the hotter climate of Vietnam, so it had to be shipped in. As a result of its high price point, only the French occupants could afford baguettes.

The bánh mì as we know it was born in the 1950s, after the French were defeated at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu. Left with many French staple dishes (but finally free to modify according to their local ingredients), Vietnamese people living in Saigon are said to have created the sandwich as the antithesis to the popular French baguette sandwich. In the bánh mì, vegetables replaced the expensive cold cuts, and mayonnaise was used in place of butter.

The bánh mì only found its way to America after the Fall of Saigon in 1975, when millions of Vietnamese people fled their home country for new ones — like the United States. There, many immigrants opened restaurants to feed their fellow Vietnamese communities, which, many years later, resulted in the mainstream American popularity of this sandwich.

4. FACT: Germany's döner kebab comes from Turkey, though Germany is still regarded as the "kebab capital of the world."

Whether you like your "vertically sliced meat" stacked high as part of a döner kebab, gyro, or shawarma, we have the Turkish to thank for the technique itself — or the Ottoman Empire, really. Chefs in the Ottoman era realized that roasting meat vertically resulted in a much more even cooking process, and in addition to the drippings basting the meat without any effort on the chef's part, it also kept the fat from dripping directly into fire. Animals had previously only been roasted horizontally, which usually resulted in excessive burning due to flare-ups.

After World War II, thousands of Turkish people found themselves in post-war Germany to participate in the country's "guest worker" program, and today there are over 3 million people with Turkish roots living in Germany. It's no surprise then that the ultra-popular döner kebab was first introduced to Berlin by Turkish immigrants. How popular, you ask? Well, there are now over 16,000 kebab shops in Germany — which is far more than the number of kebap stores located in Turkey itself.

5. FACT — The concept of battering and frying fish (which ultimately became the fish and chips commonly associated with the UK) was actually introduced to the British by Sephardic Jewish people fleeing the 16th-century Inquisition.

Brief history refresher: The Inquisition, run by the Catholic Church to punish "heresy," was felt most intensely in Spain and neighboring Portugal, where Jewish and Muslim people were persecuted, tortured, and often executed over a period of 200 years.

Frying fish checked a number of boxes. Since Christians wouldn't eat meat on Fridays anyway, eating fish was a seamless way to integrate into the country's upheld customs. Fish is also considered pareve in the Jewish religion, which also made it a seamless way to avoid non-kosher foods. Many would even save leftovers to eat the next day, so as to avoid cooking on Shabbat.

As for the "chips" that were ultimately added to the iconic fish and chips duo? The exact history is a bit unclear, though many credit the addition to Ashkenazi immigrant Joseph Malin — who opened the first fish and chips shop in 1863. Over 150 years later, there are now over 10,000 fish and chips shops across the UK. So, it's safe to say that this delicious meal, once intended as a means of integration, has become completely intertwined with modern British culture.

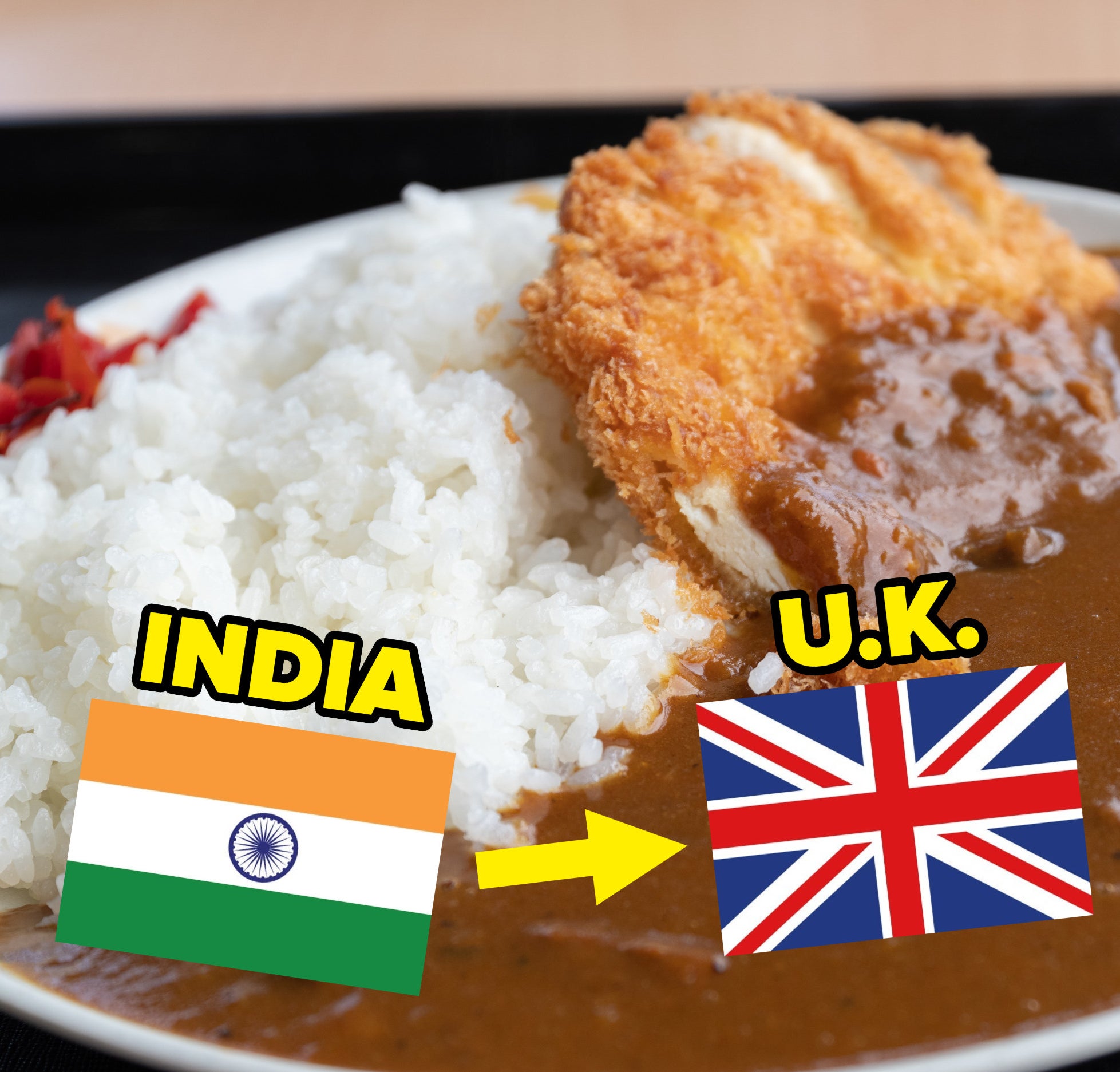

6. FACT — Japanese curry is actually inspired (and heavily influenced) by British curry, which is in turn derived from traditional Indian curry.

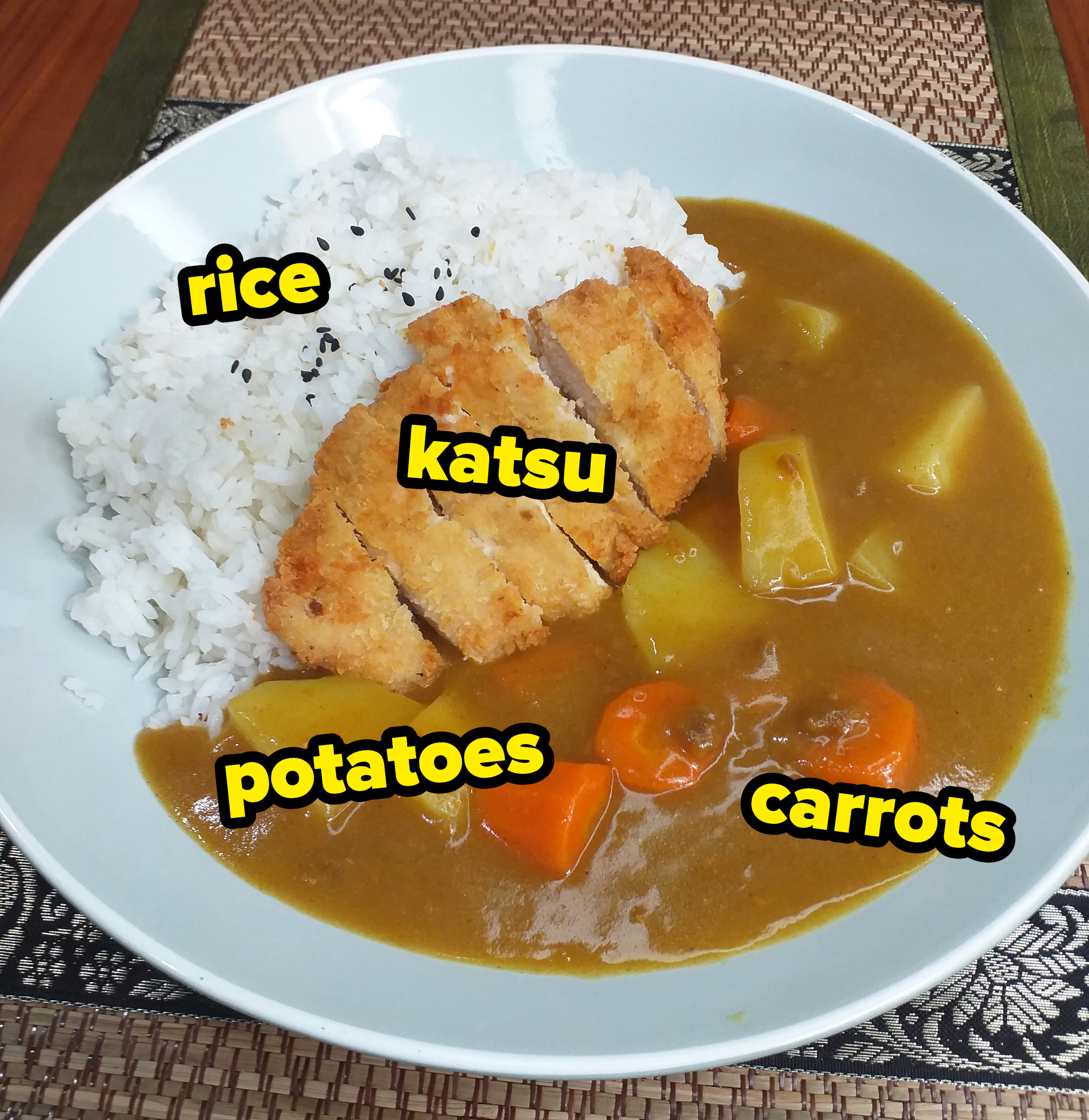

If you've ever spent time in Japan, you'll know that Japanese curry (sometimes referred to as "curry rice") is a major part of the country's culture — and with unique varieties prominent in many different regions of Japan, you could easily categorize it as a national dish. However, this sweet and savory staple actually has roots in the UK, and their version is actually derived from popular Indian curries.

In the nearly 100 years that India was ruled by the British, a unique "Anglo-Indian" cuisine emerged, both from Indian cooks re-interpreting classic British dishes, and from the British colonizers who tried to anglicize popular Indian ones (think: butter chicken becoming British tikka masala).

As for how Indian-inspired British curry made its way to Japan? The exact origin is a little wishy-washy, but it's believed that a shipwrecked British soldier was picked up by a Japanese fishing boat, and he, in turn, brought his curry recipe with him. At first, the dish was just a simple, filling, and cost-effective dish to serve sailors, but over the course of more than 100 years, the people of Japan adapted and enhanced British curry to better suit their own palates. Potatoes were even added to the mix during a national rice shortage, and they're now a staple ingredient of the dish (alongside other components like carrots, meat, and occasionally katsu).

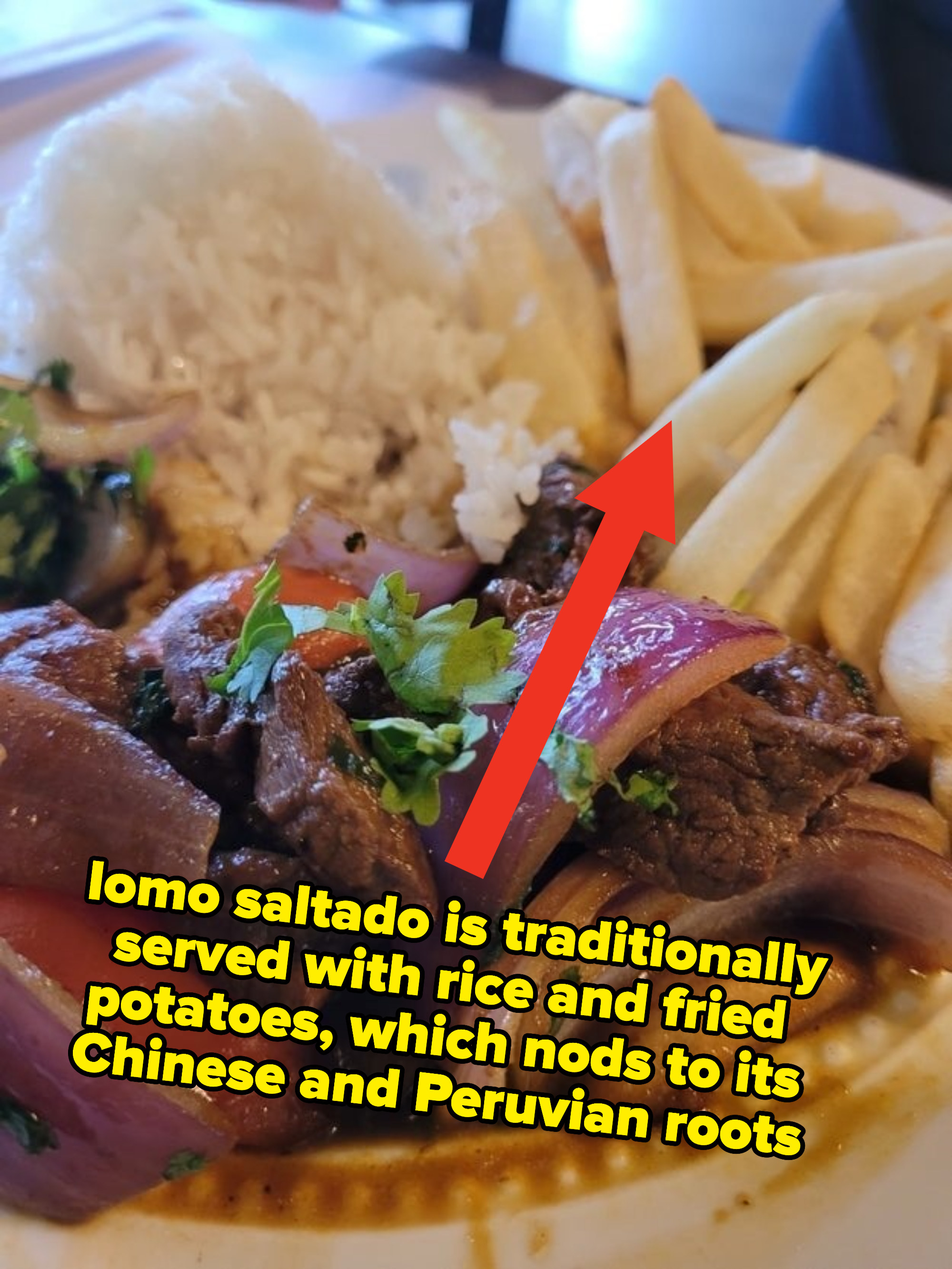

7. FACT — Lomo saltado, considered by many to be the national dish of Peru, was introduced to Peruvians by Chinese immigrants (and closely resembles most Cantonese stir-fry dishes).

In the 19th century, Chinese immigrants (mostly Cantonese) settled in Peru with the promise of myriad physical labor-based jobs, though many also worked as cooks. They brought many of their cultural cooking traditions with them, as well — like stir-frying meats and vegetables over the highest-possible heat in a wok — which paved the way for the lomo saltado that's so popular in Peru today.

This stir-fry of marinated beef and veggies is nearly identical to traditional Cantonese ones, with a few very important distinctions. Marinating the beef in a mixture of soy sauce and vinegar is a practice that's incredibly common in Cantonese cooking, but the additions of Peruvian ingredients like yellow peppers, cilantro, and tomatoes make this dish totally unique. Though the accompaniment of rice makes a lot of sense for lomo saltado — rice is a staple food in both Peruvian and Chinese cuisines — the tradition of serving lomo saltado with fried potatoes is uniquely Peruvian, considering the common crop's affordability.

If you know of any popular "national dishes" that were actually inspired by entirely different cuisines, drop 'em in the comments below! ⬇️

Note: Comments have been edited for length and/or clarity.