How I Learned To Celebrate Eid Al Adha In America

I can't slaughter a goat but I can roast a leg of lamb.

Last year, around this time, I was struggling. My Pakistani husband had moved back home to Lahore. We had both been living in New York so he could do his MBA. He graduated, our marriage failed, and I decided to enroll in a writing program online so I could stay in America on a student visa, which would buy me some time to figure out what the fuck I wanted to do with my life. I definitely didn't want to go back to Pakistan, the Land of Judgy Aunties and crappy infrastructure. I was working three jobs to cover rent and trying to write my novel at night. And that's how I completely forgot about Bakra Eid, one of the biggest holidays in the Muslim year.

In my defense, I was busy: teaching English by day, interning at a magazine, and freelancing my editing services. It was a constant hustle. Despite all that, the anonymity and freedom New York afforded me was a relief. I felt privileged to be here even if I did inhabit spaces that were alarmingly white.

In the chatrooms for my online MFA program, fellow writers would ask me things like, "What is biryani?" Or, my favorite: "I really want to be transported to this character's hometown, so can you talk a little more about the smells, the sounds, and the food?" It was all about the food. "Something that'll really make the exotic nature of this city real to me."

But I didn't want to. No one had explained to me what apple pie was growing up, yet I was expected to have a perfect grasp of the Western literary canon that went on endlessly about Christmas and Thanksgiving feasts. Now, I was the one writing. I wanted the privilege to write biryani without explanation. I didn't want to have to exotify what was ordinary to me, for someone else's comfort.

There was a boldness in my replies that came easily from behind a screen. When I wrote back to my online workshop peers, I would say things like, "I think the audience I'm writing for understands what I'm saying."

But the same boldness evaded me in real life, when I would walk into the offices where I read transcripts and wrote stories. There, they could see me and the color of my skin. And despite being light-skinned, depending on what was in the news that day, I would feel more or less vulnerable.

I bent over backward to explain myself. "From Pakistan," I would say. "Not a terrorist," I almost added. But I didn't — the joke would only be funny if racial profiling didn't exist.

I developed an inner filter. I rarely wore salwar kameez. Before talking about any cultural practice I would ask myself, Does this make us sound violent? There was already enough of that in the news. So I stopped talking about Bakra Eid, the day Muslims all over the world slaughter goats and feed their friends, family, and those in need. I got tired of explaining why I wasn't eating from dawn 'til dusk during Ramzan. Explaining Ramzan would mean claiming my Muslim (but not terrorist!) identity. When did I become so fiercely protective of it? I was keeping it tucked away so deep inside of me that it started to disappear. I stopped fasting altogether.

One Tuesday night last fall I got a text from H, a fellow Pakistani writer who was supposed to be meeting me at 9 p.m. at my apartment in Astoria: "Running late."

It was 8:45. She was still an hour away. She was always late. I was pissed.

"FINE," I wrote back, exasperated.

"By the way, Eid Mubarik," she wrote.

I stared at my phone. How had I forgotten? Then I remembered the multiple missed calls from my parents that week. Shit.

"Fuck. I totally forgot."

No response, she was on the train.

I thought about it for a second, then wrote, "Let's go to Jackson Heights?" She would get it when the Q train came above ground.

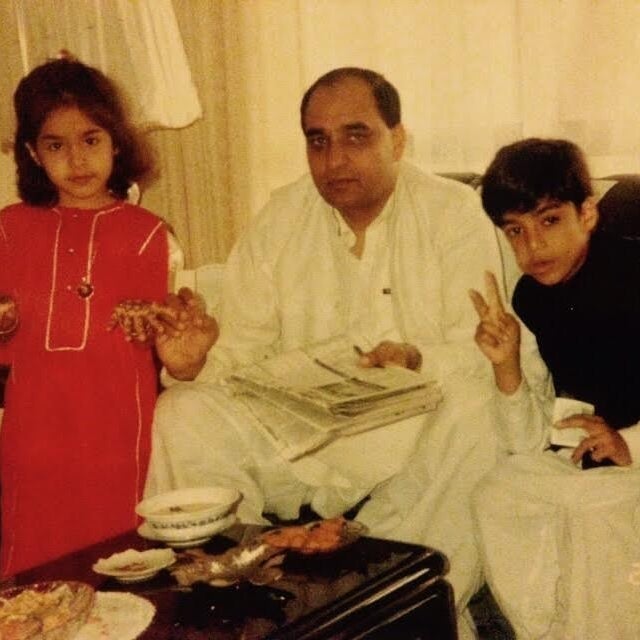

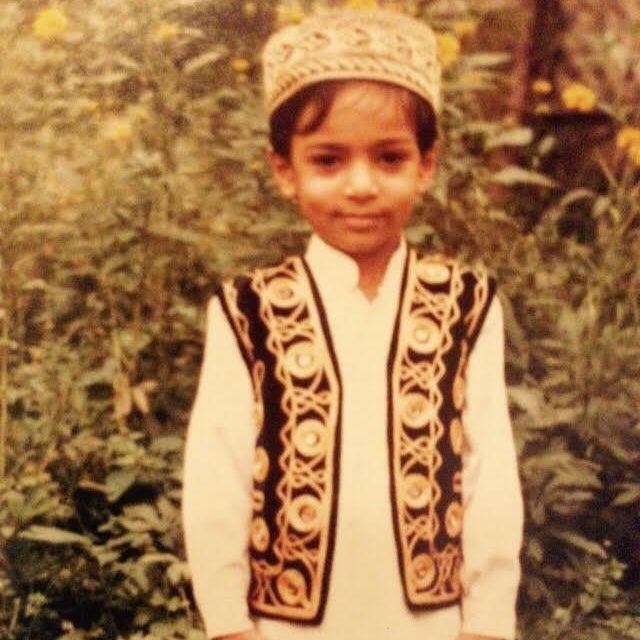

Above: The author, her parents, and brother celebrating Eid in the 1980s.

I spent the next 30 minutes remembering Eid at home: The bleating goat that would be tied to a tree on my front lawn. It would be fed and tended to for three days and then slaughtered on the morning of Eid, right there. Every day after school, I would hang with the goat. It was kind of cute with its floppy ears, beady eyes, and mouth that zippered back and forth to chew corn. The first time I saw a goat being slaughtered at age 6 I was horrified. "I know you're sad and that's OK," ama said. "We're doing this in the spirit of sacrifice. Now you know there's something bigger out there."

"And also, don't get so attached to your food," my brother quipped as rivers of almost-black blood flowed into our lawn. "Good for the grapevine," Abu would say. And later that year, when we ate the deep-red grapes, I wondered if they got their color from the goat's blood.

"LET'S DO IT."

It was H and she was down to go to Jackson Heights, New York's Desi capital. In our trackpants and sweatshirts (it was already late), we headed to Dera Restaurant. On the way, we snickered to each other about culture-shocking the more traditional Pakistanis that lived in Queens.

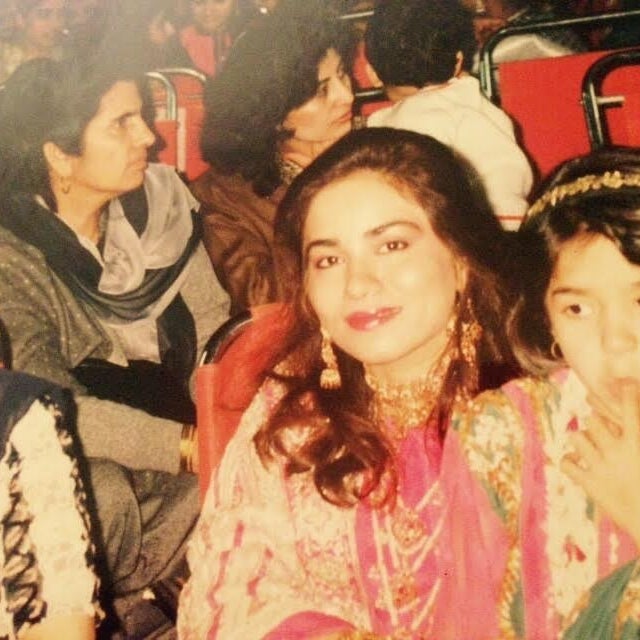

When we got there, the party was in full swing: Desi aunties in their shiny, bright Eid best, wearing bedazzled kameezes. That, we expected. But then we saw the women in tiny dresses wearing bangles on their tattooed arms, bindis on their foreheads. They gave zero fucks. Whatever internal filters they had, they were definitely wearing what they wanted. They were claiming their identity in ways I couldn't. I ate kebabs and haleem with a side of shame. I was ashamed for forgetting Eid — not just because my ama would be furious, but because I should love myself more than that. I was ashamed for giving up so much of myself in an attempt to be accepted. But most of all, I was ashamed for eating my Eid dinner in trackpants.

The next day I called my ama and told her I celebrated Eid by going to Jackson Heights. I made it sound like it had been a big elaborate plan that I had made with my many friends.

This year, things are different. I found a full-time job, a way to stay in New York, and more friends. This year, I looked forward to Eid like I did when I was a child. I didn't slaughter a goat in my nonexistent back yard, but I made my parents send me photos of the goat. And I did find a halal butcher (Yelp to the rescue) and called him.

"I need two legs of lamb."

"Sorry miss, we don't serve meat to people we don't know," he said.

Was this guy for real?

"I need them for Eid. My name is Zainab."

I leveraged my Muslim capital. He paused.

"When do you need it?"

When I arrived at the butcher shop, everyone was staring up at a tiny TV. A Premier League game was on: Swansea City was unexpectedly beating Manchester United and not much time was left. I waited for the game to be over, and then caught the attention of a guy behind the counter. Yep, he was the one I had spoken to on the phone. He was much warmer in person. He brought out half a lamb from the freezer; the legs still had to be separated.

"Could I take a photo?" I asked.

"Yes," he said. "Take it with my son in it."

The butcher's son abandoned the meal he was eating and posed in front of the half-lamb, smiling broadly. When the butcher rang me up he pointed to the guy sitting behind the till. "Take a photo of him."

"We're the oldest halal butcher in Flatbush. Been here for 26 years," the guy said, beaming proudly.

I called my ama for recipes and she told them to me over the phone as I jotted them down. We were both used to this. I marinated the lamb legs overnight and spent the next day cooking a meal similar to the one I would have eaten at home. My favorite part of the process was stabbing the leg and rubbing the marinade into the meat. I've always loved working with my hands without utensils. I made aloo-gobi (potatoes and cauliflower), a dish that is not commonly found at an Eid dinner, but my ama loves vegetables. I couldn't not have it. I invited friends over to eat with me, and each of them brought something, like we do in Lahore.

Maybe some day I'll even tell you the Qur'anic legend behind the sacrificial goat. But for now, this is my story. And America: I'm only just getting started with you.

THE MENU

MAKE THESE:

Cauliflower With Peas, Carrots, and Potatoes

Condiments: Raita and Mint Chutney

BUY THESE:

Samosas

Naan

Achaar (pickle)

Gulab Jamun (South Asian doughnuts in sweet syrup)

Prop credits:

Wood Square Sauce Dish, Acacia Wood Oval Tray, Irish Coffee Mug, vintage oval green floral plate, pink floral platter, and green circle platter by Fishs Eddy. Astier de Villatte Adelaide Large Dinner Plate by ABC Carpet & Home and Tibetan shawl/scarf (2) by the Tibet Shop at ABC Carpet & Home.